The Lake Powell Pipeline is History! Onward . . .

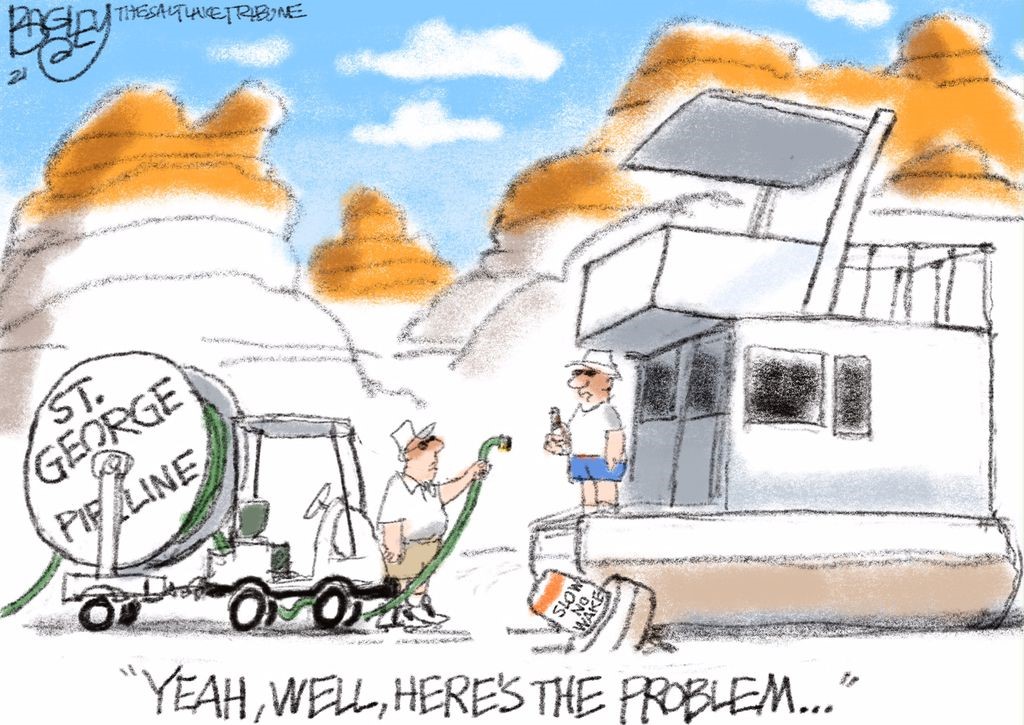

The Lake Powell Pipeline (LPP) is a disastrous proposal to pump 28 billion gallons of Colorado River water per year to Southwest Utah. The water would be pumped 140 miles away and 2,000 feet uphill from Lake Powell to Sand Hollow Reservoir in Washington County, all at an estimated construction cost of $2.4 billion. Just one snag: there is no water available for this antiquated and out of step approach to water management.

The Reality

The LPP project is detached from reality. Utah cannot count on any additional water being available from the Colorado River, and building the LPP makes no sense without a guaranteed supply of water to draw from. Instead of facing this harsh truth, the pipeline represents the old mentality of water management in the West – build big, waste big, environment be damned – which nature has now demonstrated is completely unviable. The original 1922 Compact overestimated the Colorado River’s annual flow, and climate change is aridifying the Southwest, further reducing the river’s already over-allocated water. Utah is desperately trying to cling to its share under the 1922 Compact, but the reality is that all seven states will have to adjust to permanently lowered Colorado River flows.

Moreover, Utah’s water rights are junior to those of other actors including California, Arizona, Mexico, and several Native American tribes. This means that even as the pool of available water shrinks, those other actors legally must get their shares first – leaving Utah’s prospects of water for the LPP volatile at best, and most likely non-existent from day one. Of note, all six other Colorado River Basin states objected to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement process for the LPP in 2020, bringing it to a halt.

Even if there were ample Colorado River water available, the LPP is entirely unnecessary and very expensive – it’s not even close to an option. Washington County is growing in population, but it’s among the most wasteful water users in the entire country, at 275 gallons of water per person per day (gpcd). This is twice the national average of 138 gpcd and much higher than most of the Southwestern U.S., including cities like Las Vegas (110 gpcd) and Phoenix (111 gpcd).

Extremely cheap water prices are partly to blame, as well as the lack of a commonsense culture of water conservation here in the desert. According to the Washington County Water District, only 20% of its water deliveries are supplied to homes and businesses for necessary uses, while the other 80% is “secondary water,” which is used for unnecessary purposes like watering the lawns of municipal properties, cemeteries, and houses – again, in the desert. Simple water conservation steps could reduce Washington County’s water usage faster, easier, and more reliably than building this expensive and unnecessary pipeline. Southwest Utah has adequate water from existing sources to grow smartly in the coming decades, if it does so sustainably.

The Lake Powell Pipeline would also be far more expensive than implementing basic water conservation measures. Its cost has grown significantly, from $187 million in 1995 when it was first conceived to $354 million in 2006 and now an eye-watering $2.4 billion. The monumental economic burden would fall on Washington County residents, but the state of Utah would also end up paying annual financing installments, taking resources away from more important priorities.

Last but certainly not least, constructing the LPP and its associated infrastructure would be an environmental disaster. It would scar scenic landscapes, block wildlife movements, and disturb archaeological sites along the route. A temporary water well would be drilled every 5 miles to provide water for construction. Proposed new structures include six hydroelectric plants, each 25 feet high, with power lines, cell towers, parking lots, new paved access roads, fencing, regulating tanks and reservoirs, plus chemical rooms at each pumping station to prevent quagga mussels from spreading. This would all of course need weekly maintenance after construction ends. And keep in mind, the alternative is basic water conservation, with no environmental destruction whatsoever.

What’s Next?

In fall 2020, amid major pushback from NGOs and the public, plus the threat of legal action by the other six Colorado River Basin states, LPP proponents were essentially forced to put the project on pause as they scramble to find a path forward. In 2021, the Utah legislature then created the Colorado River Authority of Utah to lobby for the state’s full water share in future negotiations, including for the LPP. The pipeline is currently on the backburner – down but not out. CSU will remain vigilant in monitoring any attempts to revive the LPP.

In the meantime, the current Bureau of Reclamation’s Interim Guidelines for the Colorado River Basin States are in effect until 2026. The seven states and the federal government will have to reach agreement on the subsequent rules to manage the river’s declining flow amid historic droughts and climate change. The Bureau of Reclamation, by their own admission, is in uncharted waters with trying to figure out, in the face of Lake Powell potentially reaching deadpool status, how to ensure the water supply can proceed downstream for 40 million people. So Utah will by no means get a free pass to divert imaginary water for the unviable LPP, but that won’t stop the state’s politicians from trying anyway!